Three acts. Five acts. Sometimes as many as seven acts. Whatever the number, this structure is all about tension. It rises. It falls. The transition from one to the other is a climax point. This is usually the first structure anybody talks about when listing types of structure. Sometimes it’s the only structure talked about. Most instruction on screenwriting, for example, is oblivious to the possibility of another type of structure.

This structure is so common that the image of it has its own name, Freytag’s Pyramid.

If you understand “rising action” and “falling action” as descriptions of tension, this is pretty straightforward. Variants on this image are pretty common, too. Some will put exposition on an incline instead of giving a flat line; usually it’s a shallower slope than the “rising action” but not always. Others will tilt the pyramid to the right, indicating a slower rise in the tension and a steeper drop-off after the climax. That’s particularly common for thrillers and mysteries. It’s also common to see the left-hand line broken up into mini-peaks or rises, indicating that the tension doesn’t increase smoothly or that there are pseudo-climaxes on the way to the peak. You might also run across depictions where the flat line for the denouement is higher than the flat line for the exposition, indicating that the tension built over the course of the story isn’t fully released. That last might show up when the book is part of a series and there are still things to resolve, or when the new status quo is less comfortable or stable than the one encountered at the beginning of the work.

All these variations demonstrate the handy flexibility of this structure, but they don’t fundamentally change the underlying structure, which is that rise and fall of tension. Thinking about the ways to tinker with the image, and by extension, the structure, is handy both for helping pick apart a work that doesn’t quite fit the graphic, or for planning your own work.

But while Freytag’s Pyramid is a great, intuitive way to capture the X-Act structure, there’s another graphic that shows up almost as often in the structure section of how-to writing texts.

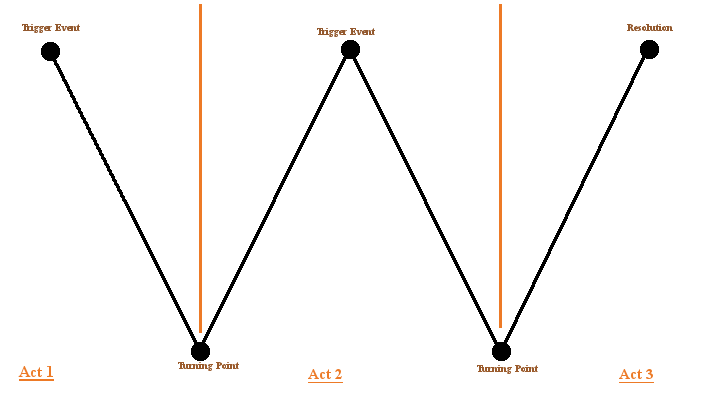

This W-structure lays things out as a series of turns, rather than a smooth rise and fall with a single inflection point. It still marks act boundaries, but the preoccupation here is with try-fail cycles, major revelations, and plot twists. Tension doesn’t play into this at all.

If this W shape represents the X-act structure without a rise and fall, or even a nod to tension, does this undermine everything we’ve said so far?

Not really.

How can that be true?

The answer is lurking in the full name usually given to charts of the W-structure: The W-plot structure. Plot is independent of the structure of a piece (though they interact with each other a lot) so a picture of the plot doesn’t necessarily look anything like the structure of the piece.

If you want to, you can map the W-structure onto Freytag’s pyramid quite nicely. The “trigger event,” also known as the “inciting incident” shows up during the flat exposition line. The first turning point marks the transition to rising action. The second trigger event comes ahead of the climax, (the rising slope might get steeper after this), the next turning point is the climax, and the resolution lands on the denouement.

What’s really neat here is that while the W-plot structure is usually taught as a representation of the typical X-Act structure, the relationship between the two isn’t required. You can have a completely different plot structure that maps onto Freytag’s Pyramid, or map a W-plot onto a kishotenketsu structure. What you get when you do that will be different from what you might expect, but can still be a successful work.

This striking contrast between Freytag’s Pyramid and the W-plot structure is useful for seeing the difference between “plot” and structure, but it also illustrates a critically important concept for approaching critical analysis: what you’re looking at or trying to learn will radically shift what you get as a result. A work that perfectly aligns with both images might have a third completely different image if you depict the protagonist’s character arc. Teasing apart the different elements at play in a work and being able to look at them in isolation is key to understanding their function, as well as figuring out how they interact with each other. Get comfortable with thinking flexibly about ways of depicting and conceptualizing these different elements, and creative with the approaches you’re willing to take, and you’ll be much, much more effective at getting insight from the things you read.