Confessions of a Mask: Unlayering its Structure

This post will be a detailed analysis of Yukio Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask. If you haven’t read it, a lot of the specific details discussed here won’t make sense. However, a lot of the broad points should still be useful, and if you’ve read other works with a Kishotenketsu structure, you might be able to apply the specifics here to those examples.

In the last post, we reviewed the four acts of a Kishotenketsu structure. It’s very easy to see those acts play out in Confessions of a Mask because it very handily has four chapters, each mapping onto one of the acts. All four chapters work together to give us a deep, moody focus on the inner life of an isolated homosexual, biromantic man growing up in Japan in the lead-up to and during WWII. Everything on the page in this book is dedicated to introducing, illustrating, and complicating the reader’s understanding of that character.

The first chapter, the introduction, not only introduces the novel’s protagonist and main preoccupation of the text - his interest in men - but it also introduces images and details that foreshadow and enhance the content as the book unfolds. There are three particular elements from this chapter it’s valuable to focus on for our purposes here:

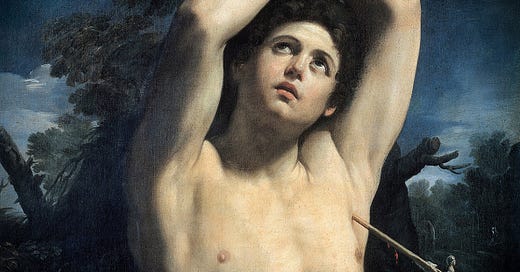

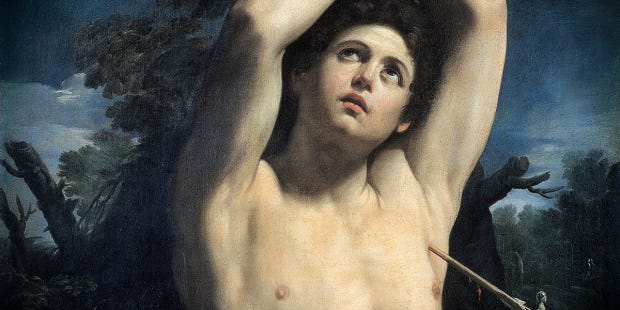

His interest in St. Sebastian (Not only is his interest in a naked man being violently penetrated a foreshadowing of his later sexual interests, but St. Sebastian is a bit of a gay icon, something our child protagonist didn’t know but Mishima most certainly did.)

His initial fascination with, and rejection of, Joan of Arc (Foreshadowing his interest in Sonoko, and ultimate failure to have that go anywhere.)

The bizarre isolation of being raised by his ailing grandmother while a sickly child himself. (His sickliness enables many of the key plot elements later, and the isolation established here only intensifies over the course of the book.)

These are the primary tools of the introduction, and their role evolves over the course of the narrative in keeping with the needs of the book’s structure.

The second chapter, development, is a very explicit deep dive into the protagonist's sexuality. It opens with a focus on his experience of puberty, and focuses not only on his first crush on a classmate, but also his burgeoning dedication to the romantic ideal of an early, violent death. Plus there’s a stop for a detailed fantasy about cannibalizing a beautiful youth. There is no doubt, by the end of this section, that our protagonist is a queer man who has no idea what to do with himself other than retreat in to fantasies of machismo, and that he has no cofidence of living up to those fantasies.

Which is why the third, twisty chapter, where he seems to sincerely fall for Sonoko, his friend’s sister, is a twist. When they’re together, he sincerely enjoys Sonoko’s company. They have a real friendship that he enjoys, so long as it’s never expected to be anything other than a friendship. The moment marriage and sex come onto the scene, it becomes Joan of Arc all over again, a woman in men’s clothing, and something he firmly rejects. The chapter doesn’t settle for twisting our understanding of his sexuality on that axis, though, as this is also the section where his aspirations of dying in war fall apart and he realizes that he might actually prefer to live; he doesn’t have what it takes to live up to his masculine ideals.

Which leaves us with the final chapter, where we conclude the narrative. We don’t resolve anything; he’s still lonely and isolated, still sexually unfulfilled, still unable to live up to the masculine image he romanticizes and desires. In effect, everything introduced to us in that first chapter is still present and unchanged in this last chapter, but the reader’s understanding is much deeper, and significantly more nuanced, that it was after that introduction. The final scene, where he’s dancing with Sonoko as part of their sexless affair, she thinking this must ultimately develop into adultery while he, oblivious, checks out the handsome young men off to the side, means far more than it possibly could if it had come earlier. Joan is in his arms, St. Sebastian is off to the side, and his isolation suffuses everything.

That isolation, and the intensely introspective voice of the narrative, contribute to the successful moodiness of the novel. The consistency of the mood here is a feature of the narrative; it doesn’t arc, it intensifies. This is a common effect to find with a Kishotenketsu structure, and if that’s your goal with a piece, would be a good reason to choose this as your structure.